Painting, drawing, and image theory in the work of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe.

“The purpose of art is not to reproduce the outward appearance of things, but their inner meaning.”

The multifaceted genius of Goethe is often associated with the paradigm of the “universal man,” the embodiment of the humanistic ideal of the literary scholar and scientist. However, within the scope of his activity, his contribution to the visual arts has long been neglected compared to his literary corpus and naturalistic research.

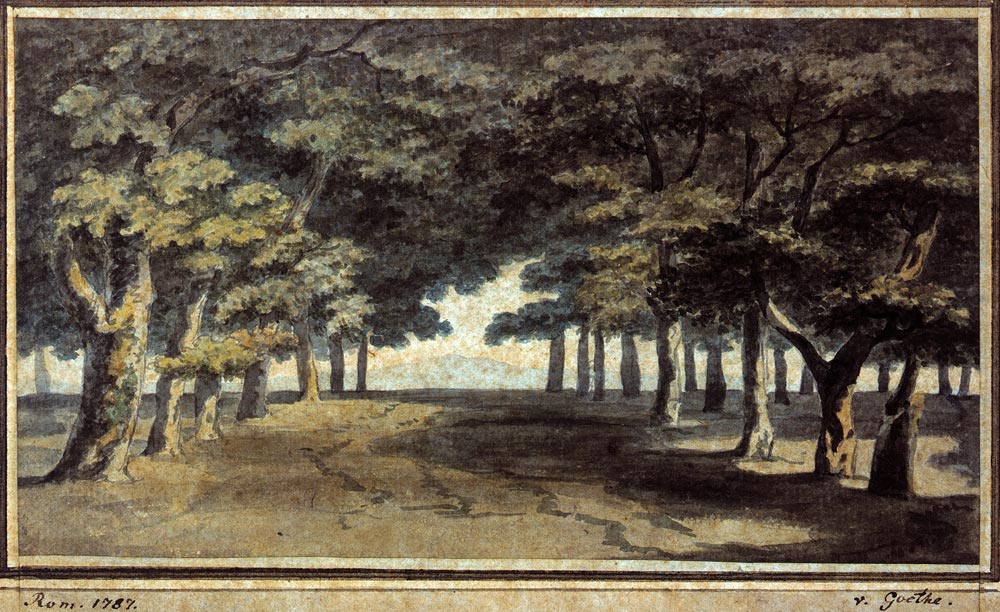

Although he himself claimed to have “no talent for visual art,” Goethe was also a skilled painter and draftsman—a passion he cultivated throughout his life, intertwining his love for nature, science, and aesthetics with the creation of visual works of considerable value.

He developed a significant graphic and pictorial practice that has received growing attention in interdisciplinary studies. Thus, his drawings, watercolors, and studies from nature have been reevaluated—not merely as personal documents, but as an integral part of his aesthetic and cognitive research. For him, drawing represented a means to explore the natural world and reflect on himself as a man and artist. Driven by his profound curiosity for every manifestation of Nature, Goethe used drawing as an instrument of knowledge, a way to “see more clearly,” to grasp the archetypal form (Urbild) behind phenomena. In this respect, his artistic activity should be interpreted as part of a broader morphological project. Indeed, his attention to detail and precision in representation is striking, accompanied by an aesthetic sense that renders his works not only study tools but also genuine artistic expressions.

His travels in Italy, a land that deeply captivated him, sharpened his interest in the visual arts, under the influence of classicism, archaeology, and direct encounters with Renaissance and ancient works. He found inspiration in the Mediterranean light, architectural forms, and the beauty of landscapes. In his sketches, one can observe views of Rome, Naples, and Sicily, often characterized by a lyricism that reflects his poetic sensibility. These works did not aim for a photographic reproduction of reality but to capture its emotional and symbolic essence.

From a technical standpoint, Goethe’s style is certainly less refined compared to that of great masters, but his works reflect the depth of his reflections on visual perception and the interaction between light and color. His works reveal a disciplined hand, more oriented toward analytical observation than emotional expression. He favored the use of charcoal, ink, and watercolor, but deeply appreciated color and devoted much of his life to studying its properties through his Theory of Colours (Zur Farbenlehre). Painting was, for him, a way to put his theories into practice and experiment with the principles he had formulated.

Until the 20th century, Goethe’s painting activity was considered secondary or amateurish. Only with the rediscovery of interdisciplinarity in early 19th-century German thought—and particularly with the Kulturwissenschaft approach—has criticism begun to recognize the intellectual value of his graphic work.

Though less well‑known, his visual art enriches his legacy and demonstrates that creativity knows no boundaries.

Goethe Haus Palermo

A site about the extraordinary figure of Goethe.

For any comments on this page and to report any errors, please send an email to info@goethehaus.cloud.

Subscribe to our Newsletter!